The death of serendipity

All of a sudden, we’re all working from our living rooms and using remote tools and video calls to stay as connected as we can. The once-steady migration to working from home has suddenly leapt to 100% adoption. But in our collective loss of shared physical space, did we also lose all the things that come with it? Things that lead to freer, more organic conversation and feeling more together?

When we share a physical space, there's hundreds of tiny inter-personal interactions – opportunities for conversations to start – combined with a shared physical context. These give rise to something I call social serendipity: the chance for unstructured and unplanned conversations to take place. This is where people actually get to know each other, and where new ideas are born.

When designing the offices at Pixar, Steve Jobs asked that the only restrooms be placed in an atrium at the very centre of the office. Why? To quite intentionally force coworkers from across the organisation to bump into each other and mix together, striking up new conversations.

For social serendipity to really happen, you need a 'safe' environment for people to share thoughts with as little friction and consequence for a 'bad idea' as possible. When physically hanging out with friends, or sitting with coworkers that you have a good relationship with, this just happens naturally, but in a world where we all are physically distanced, something subtle is lost.

There are two main things missing in today’s social apps which are there in a physical workplace:

- A low-friction 'open channel' for conversation to flow (in an office, this is something like passively being near to others)

- Conversation hooks – exposure to things to talk about (in an office, this can be observing something that someone is doing)

Open channels

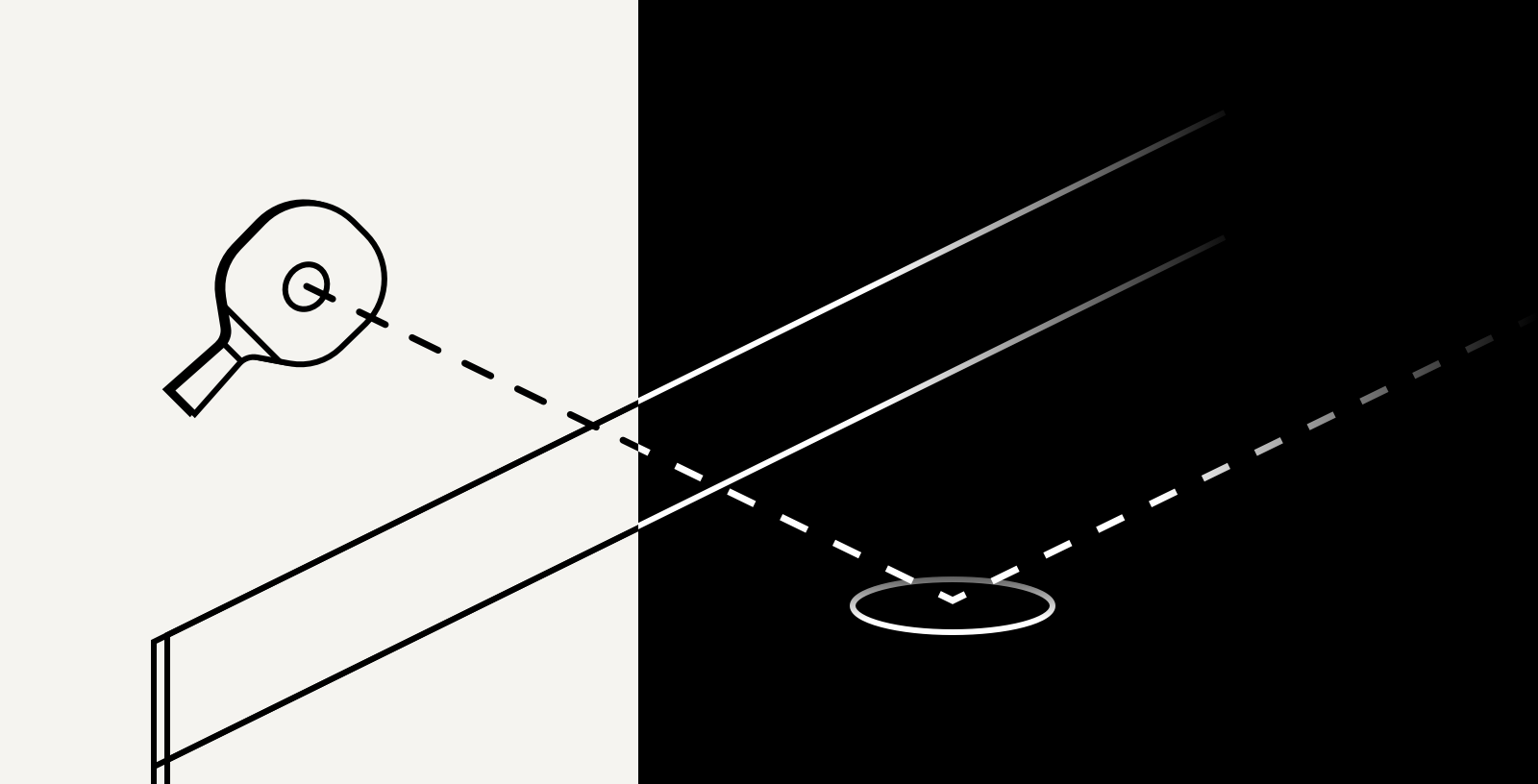

When you use Slack, email, or WhatsApp, you are effectively posting a letter to somebody. It may be fast to deliver and small in size, but it’s still a letter. This type of communication is a little like playing ping pong in the dark: you know virtually nothing about the other player’s position or current state (with perhaps the only dim lightbulbs in the room being status notifications like ‘read’,'active’, or 'typing’).

What about voice or video calls? Well, they are little more like fishing: you throw out a line and if there’s a bite, the line is connected. But this can also be quite disruptive… much like how you catch a fish and pull it out from its environment (the river), the recipient of a phone call is pulled out from whatever they were doing.

Regardless, both of these different types of communication are very intentional, and by that I mean that you need a reason to reach out and start. This 'needing a reason' forms a viscous barrier to free flowing communication.

In both cases, once a ‘session’ (what I’m calling a natural, active conversation between people) is created, people can talk fairly freely within it.

In synchronous communication (so a voice or video call), the session is formal – it has an official connect and disconnect, and everyone knows the status. Within that, people can speak freely – kind of similarly to an in-person conversation… within the bounds of the intent of the session of course, as it’s so disruptive to whatever else that everyone wants to do.

In asynchronous communication (back-and-forth messaging), the session is informal, noncommittal, and doesn’t have a clear beginning or end. There is also a kind of semi-synchronous version that can happen when multiple parties are replying rapidly, but it still doesn’t need any reason to come to an end because it’s non-committal.

If we were to put these into spatial terms:

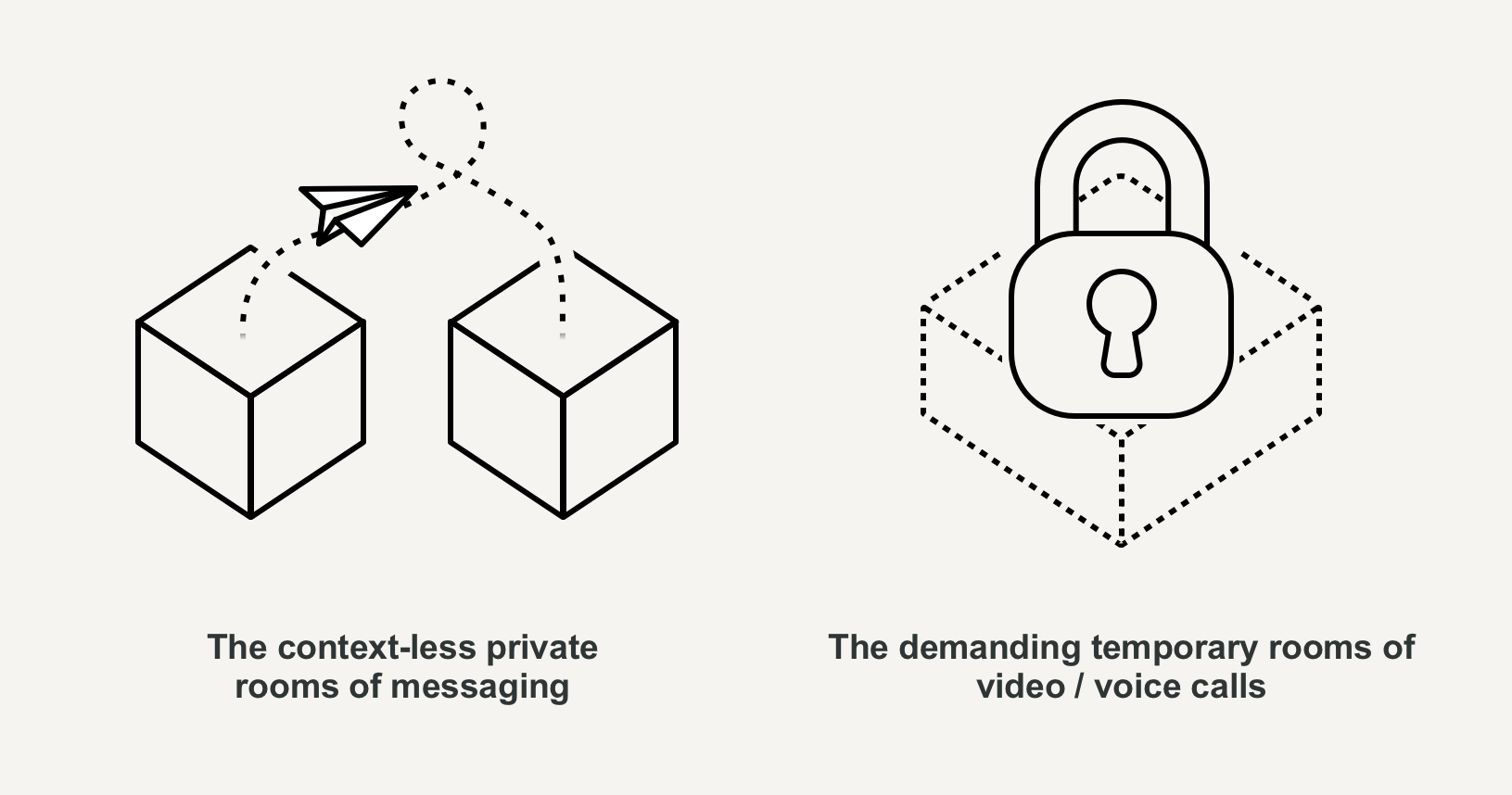

A video or voice call is like entering a temporary room – you can see who else is there, and everyone else knows you are there. However, that room also demands that you can’t be elsewhere. Because of this, they are only created if they are needed for some purpose.

With messaging, it’s like each person is inside of their own private room, receiving and sending paper letters at their convenience, each with little knowledge of when the other person will receive it, or their context when they receive it. This also means a lot of messaging is done passively by the user during other activities – there is no demand for exclusivity and so speed is something of an unknown… if you want to get something done fast, messaging is probably not the way.

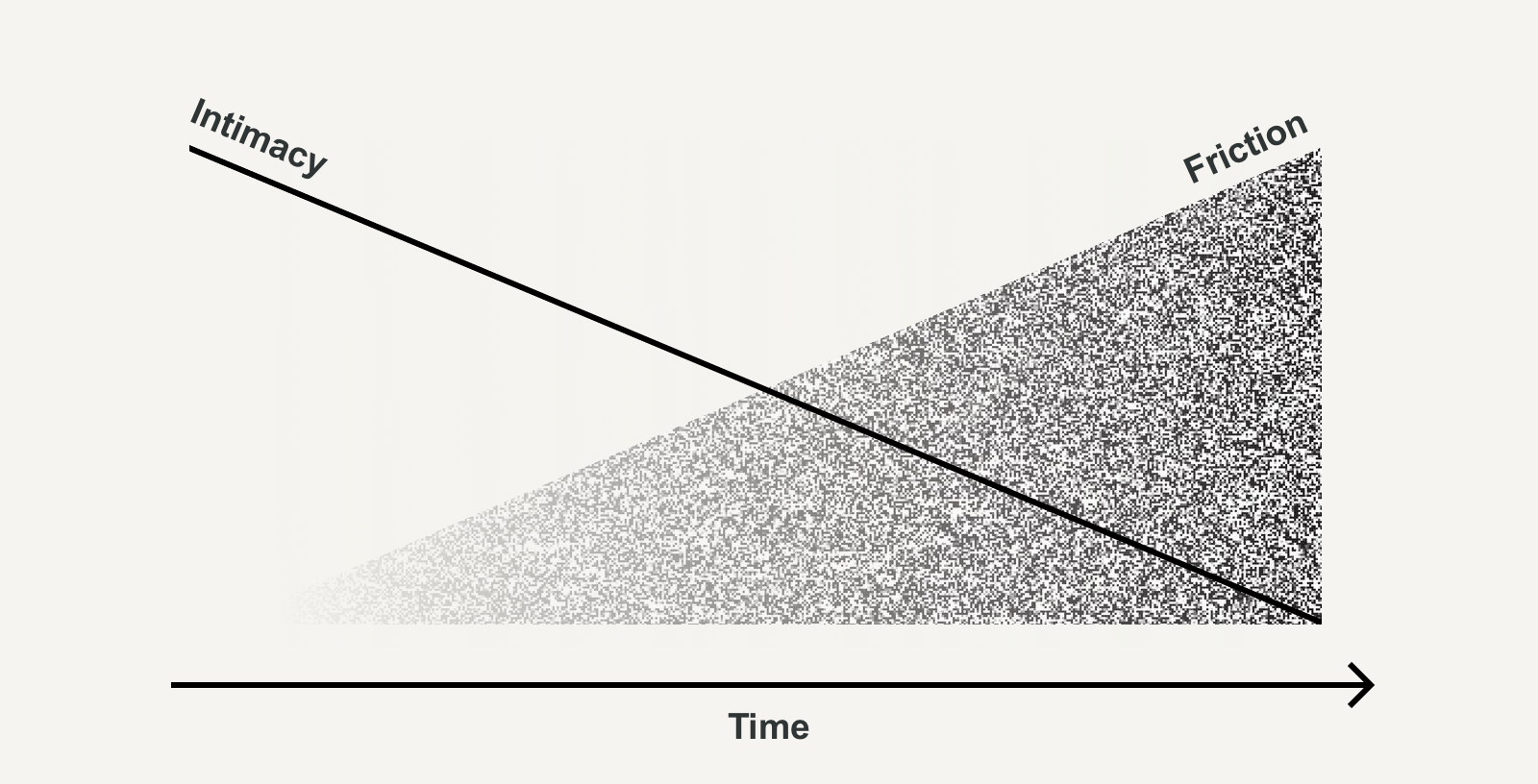

The passive nature of messaging means less demand on each party (they’re in their own space after all), but it's also less personal and involves some social friction between each batch of messages, a friction which increases directly if more time passes between batches. As that friction increases, the reason for reaching out needs to be greater and so it ends up pushing out silly, casual or free conversation for stronger reason-based messages.

However, neither of these reflect the casual nature of a conversation in an office, a coworking space, or even just hanging out. In those, people are present in a space together and are ‘open’ to conversation i.e. there is a continuous ‘session' going on, even if people don’t have to actively be engaged in it. (Note: Arguably, a more awkward version of this also happens on a conference call whilst waiting for others to join, but is short-lived and more incidental.)

This open space is fertile ground for social serendipity and natural conversation, but in remote communication, there’s still something missing: a 'conversational hook'

Conversational hooks

A conversational hook is something for another to grab onto and talk about – but when the only way of interacting with another is through very intentional methods, there’s little to no discovery of new hooks… unless actively volunteered by someone, or perhaps something stumbles into frame (e.g. someone’s dog making a surprise appearance during a video call).

What types of conversation hook are there?

Depth hooks

The more you talk to someone, the more you know about them, and the more conversational hooks you have – simply put, you just know them better and so there’s more to talk about.

Open channel hooks

In a sufficiently low friction, high trust setting, people share voluntarily – they feel comfortable enough to offer these 'hooks' up. The best example of this is just hanging out together.

Observed context hooks

If two people in a physical space bump into each other when they go to make coffee, that’s something to talk about. The same with the clothes, the weather (sorry, I’m a British cliche), the music they're playing. Our shared context powers conversation. When we aren’t able to see each other and share physical space, we have less shared context.

For consumers, Instagram Stories offers a neat solution by letting users offer up conversational hooks through low-stakes context sharing. Why 'low stakes'? Because stories are ephemeral, there is less pressure for the glossy presentation of a more permanent post so people can be more honest and less worried about their image. After all, the content won't last more than a day – a version of the 'open channel' we looked at earlier. This offers up a conversation starter that friends can latch onto, often spilling into a full chat.

The role of proximity

Real world conversation isn’t without a spatial dimension: we use proximity to control who is involved, and who is involved directly determines the type of conversation.

Conversations vary at different scales because every time we speak, we're adapting our thoughts for the audience. Whenever we speak, we’re thinking of these things:

- Who is the audience?

- What will they think of this?

- Have they understood what I’m saying?

As the group gets bigger there are more people to please, and so more people to consider how they’ll receive what you’re saying. Scale directly affects how intimate a conversation is. As the number of people listening increases, a topic gets more and more diluted or the conversation becomes more and more generic.

Effectively, as the audience grows, the soapbox that a speaker at any moment is socially standing on, gets taller and the spotlight gets brighter.

This is the reason that we often take someone to one side to be able to have a more intimate conversation. Now, this is a solved problem in many social apps because they force users to rigidly define a boundary: WhatsApp groups, Slack channels etc. all have a fixed list of members OR they're totally open (like Twitter), and there's no concept of controlling the audience.

However, in a social app that offers an open space, setting rigid boundaries on a conversation isn't the natural solution – doing that would be much more equivalent to gathering people in a particular room, and so is more intent-driven. This is fine for a meeting, but the required intent also demands undivided attention during the gathering.

The role of ephemerality

In a normal conversation setting, things aren't quite so permanent – whatever is said is heard by the audience but not recorded forever on a server.

Just imagine two conversations in a real office: one that happens normally with someone you're sitting with, and one where there's also a camera there, recording everything. Simply making that one change to the scene, adding a sense of permanence, completely changes the dynamic. A place can be transformed from a cafe to a stage: more formal, intentional... and less natural.

Of course, there's benefits to this in the right situation (a paper trail can be useful), but to recreate the organic conversations and truly open environment that allows for social serendipity, communication needs to be able to be 'throw-away' and frivolous.

This is something that Snapchat nailed for consumer social – by making things impermanent, they are free to be more natural and real.

So what's the solution?

Well, we're in the early days of remote work, but we can see clues of people's product goals and future behaviour through the workarounds they've have adopted to adapt to quarantine life. As a consumer example:

Kids get in FaceTime and don't even have their face in the camera. WHY!!!!! pic.twitter.com/p7vnjOFIR9

— Kevín (@KevOnStage) June 18, 2020

Here you can see some kids using FaceTime as an open channel to hang out in, passively leaving audio on whilst they all do different activities. What's also interesting here is not showing their faces – doing so would make it more demanding on their attention, switching the experience to an active one instead of simply 'being together online'. So far, this is probably the strongest example I've seen of digitally mirroring the casual and passive way that we hang out physically.

Have you seen any interesting workarounds used by people to create a passive shared space? If so, let me know!

I'm currently experimenting with combining these elements in building a "serendipity generator" for remote teams, a kind of shared digital space offering an open channel for conversations to happen organically.

This ongoing project is called WFH.LAND – and I would love to hear your thoughts.